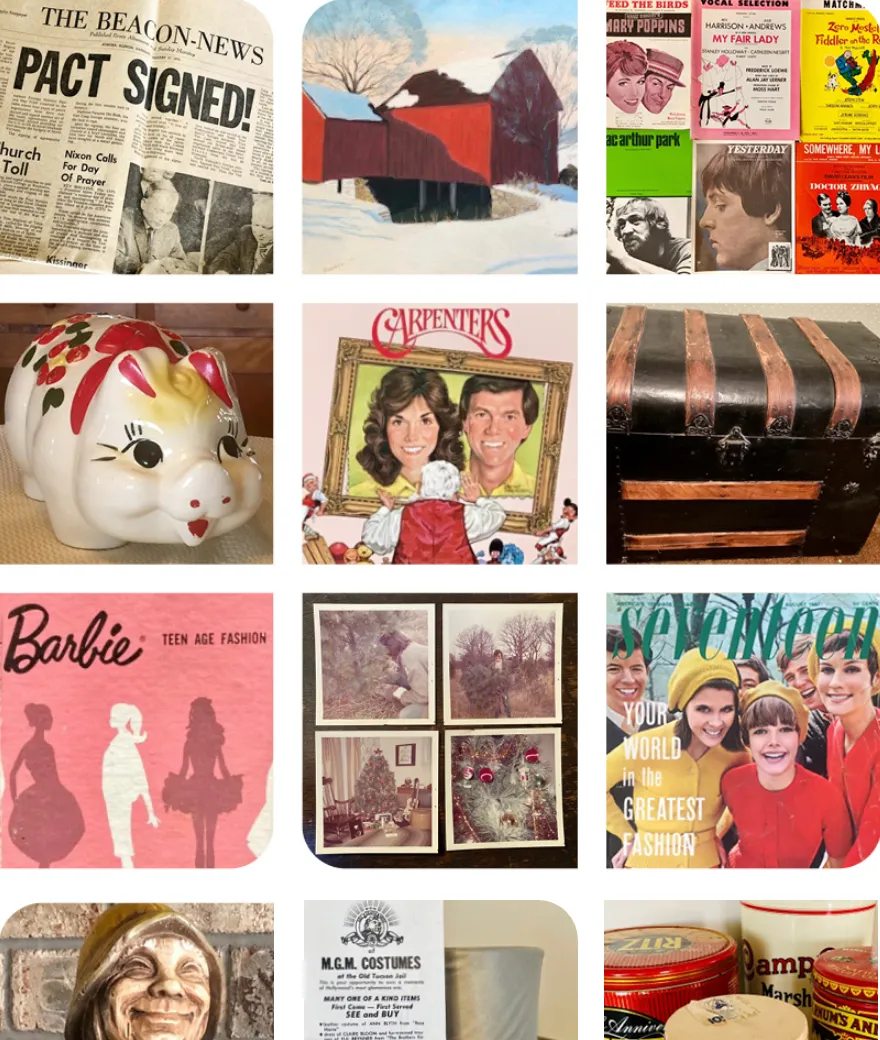

In a world where messages often zip by in seconds and memories can slip through the cracks of daily life, Artifcts offers something beautiful: a way to say “you matter” that’s tangible, personal, and lasting.

An Artifct isn’t just a photo, a story, or a digital file — it’s a love note stitched together with meaning. It’s a moment preserved in time, carefully captured and shared with intention. It becomes a topic of conversation, a happy memory shared, a new story discovered. Whether you’re celebrating a milestone, reconnecting across time and distance, or simply saying “I love you,” Artifcts transforms everyday objects and memories into meaningful expressions of affection.

How Artifcts Becomes a Love Language

At its heart, Artifcts is about connection: between family, across generations, and even between friends. When we slow down to document why something matters — not just what it is — we invite others into our world, our stories, and our hearts.

Objects gain power when their stories are told. A simple recipe card becomes a warm memory of Sunday dinners. A well-worn baseball glove becomes proof of childhood dedication. These are the stories that make the Artifcts priceless.

When you share an Artifct, you’re doing more than sending a file — you’re offering understanding, appreciation, and connection.

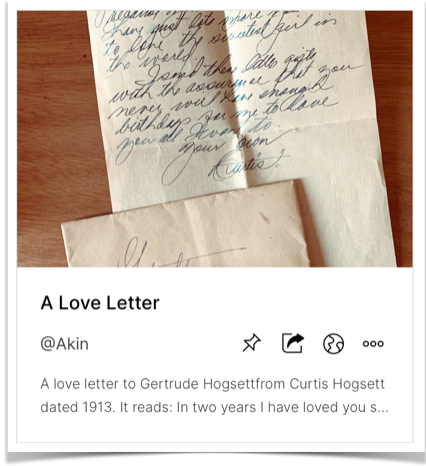

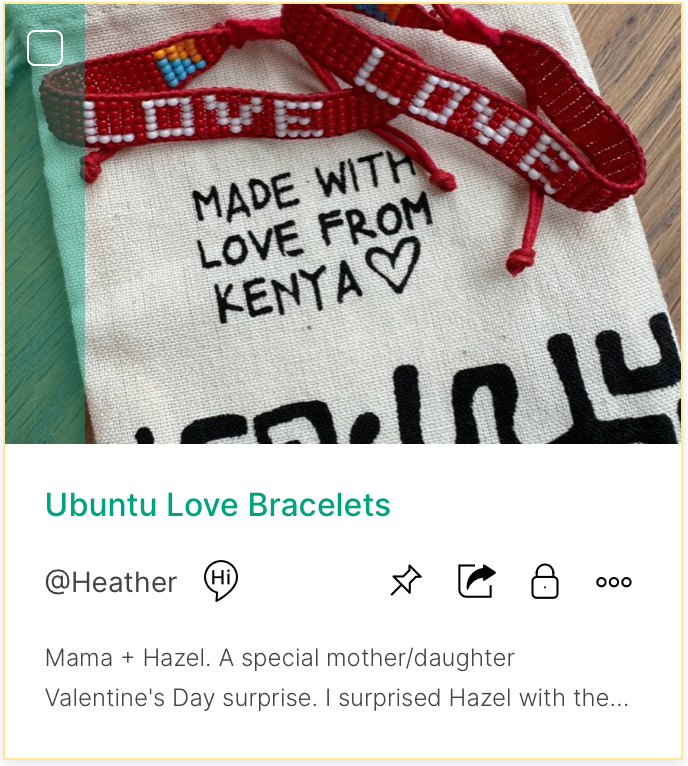

A special Valentine's Day gift from mother to daughter. Sorry, this Artifct is private!

A special Valentine's Day gift from mother to daughter. Sorry, this Artifct is private! Artifcts: Love Across Time and Distance

One of the most magical aspects of Artifcts is that it lets you share love no matter where you are. Whether family members are across town or across the globe, an Artifct carries emotions and memories in a way that text messages and social feeds simply can’t.

You can preserve:

- Family traditions and heirlooms

- Stories and mementos from loved ones who’ve passed on

- Milestones and awards big and small

- Meaningful moments and photos you never want to forget

This shared remnant of life becomes a bridge between your world and someone else’s, a shared narrative that deepens relationships and invites ongoing conversation.

Tips for Creating Truly Heartfelt Artifcts

Ready to make Artifcts that resonate deeply with those you love? Here are thoughtful tips and tricks to ensure your Artifcts are full of heart value:

🧡 1. Start With Why

Every meaningful Artifct begins with a why — a reason that goes beyond the object itself. Ask yourself:

- Why does this keepsake matter to me?

- What memory does this memento spark?

- Why have I kept this item all these years?

Share those answers as part of the Artifct’s description.

📸 2. Combine Media for Richer Stories

Blend photos, videos, and voice recordings to tell a fuller story. Hearing someone’s voice or seeing a moment in motion adds emotional depth that text alone can’t match. Whether it’s the history behind a treasured heirloom or the tale of a favorite trip, capturing details while they’re still fresh and in your loved ones own words adds richness that’s irreplaceable.

🗣️ 3. Include Personal Reflections

A heartfelt Artifct isn’t just about facts, it’s about feelings too. Take a moment to reflect on:

- What this object means to you

- How it connects to someone else

- Why you’re sharing it now

These reflections will help make your Artifcts feel personal and intimate.

🎁 4. Share with Intent

When you share an Artifct, think of it as a digital gift: add a message that tells the recipient why you chose to Artifct and share this item with them. Just like thoughtful gifts in real life, these intentional Artifcts become keepsakes of the heart.

The Art of Saying “I Love You” with Artifcts

In a culture filled with fleeting interactions, Artifcts invites us to pause, reflect, and communicate what matters most. It’s more than documentation, it’s devotion. It’s a love language for our digital age. So whether you’re commemorating a birthday, sharing a treasured family memory, or simply telling someone you’re thinking of them, let Artifcts help you speak from the heart.

This Valentine's Day as you pause for a moment to absorb all the positive in life, surprise someone—friend, sister, neighbor, professor, parent, son—with an Artifct!

Happy Artifcting!

###

© 2026 Artifcts, Inc. All Rights Reserved.