"I said I would go through it someday. I know I don’t need it all. But there it sat for over 15 years while I paid for the storage. I couldn't even remember what was in storage, much less enjoy it.” That’s what one Artifcts Community member of the boomer generation told us recently. We know she is not alone.

According to an AARP magazine review of commercial storage trends, the older you are, the longer you keep items in storage. And, on average, boomers only visit their storage units once per month. How critical is that storage? How much cost and uncertainty does it create? Maybe, we need to take a minute to talk about the proverbial elephant in the room, or in this case, the storage unit.

“Our family moved a lot over the span of 20 years, and I was in constant survival mode. There was no time to ponder what we kept and what we let go of much less the good stories to pass on,” said another Artifcts Community member. He then proudly (or rather sheepishly) shared that that is how they ended up one time moving a trash can still full of trash.

He was trying to justify to himself why he and his partner kept moving the same ‘stuff’ from house to house, even if only to put back in storage in the next garage, closet, and attic. (And that eventually became a downsizing adventure of epic proportions. Read about it here.)

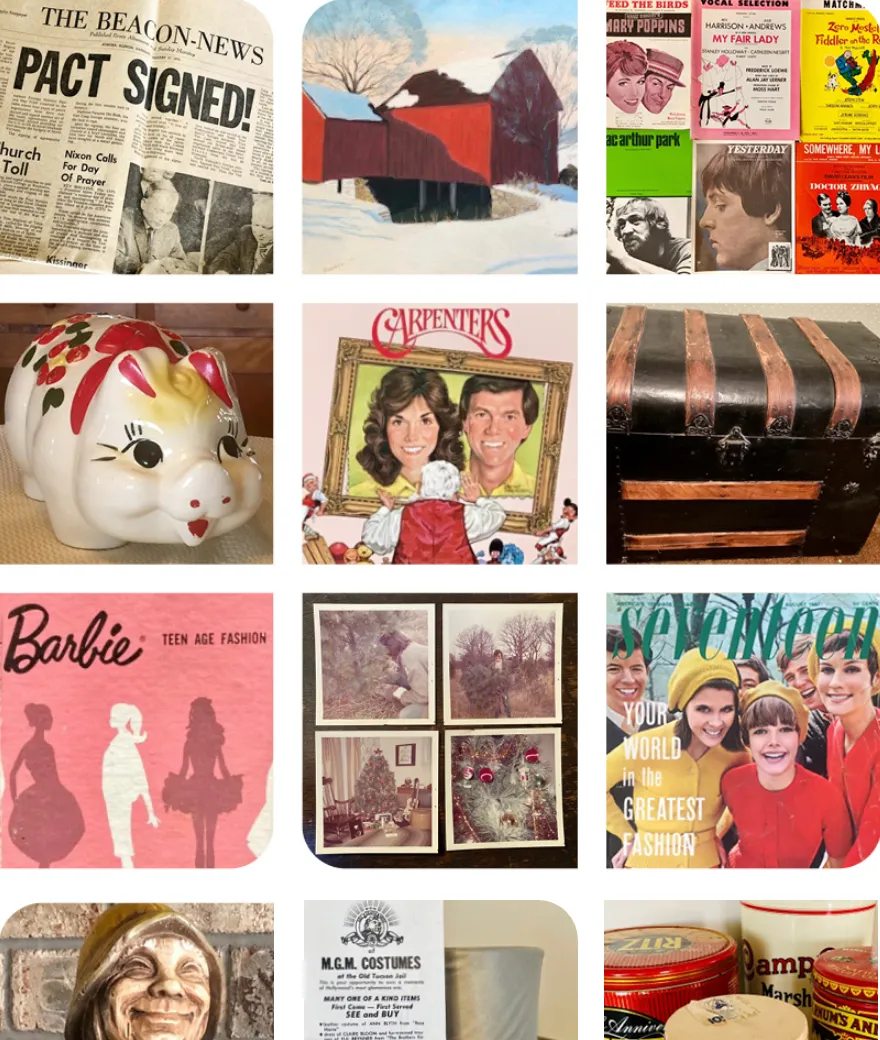

We have also heard from people who held onto items and expressed some version of, “Surely it will still be worth something, and I can sell it,” only to find it degraded over time in the hot attic, the style or material was no longer in vogue when recovered from the basement, or some other reason meant that no, it was a lost cause. And still others have confessed to using storage for items and sometimes nearly whole estates they have inherited and did not have the time, interest, or heart to go through.

Sound familiar? Or think you're immune? Given today's demographics and the impending great wealth transfer, we are all at some point going to have to encounter this very dilemma--too much 'stuff,' not enough space, and the desire to preserve and share the family memories and stories behind those keepsakes.

How to Make the Most of the Money We Spend on Storage

Keep in mind, storage is not always at an offsite property where you pay a monthly fee. Want to talk about expensive storage, consider the climate controlled space you live in!

#1 KEEP TRACK OF WHAT YOU STORE

If nothing else, make a list and take pictures of the bulky and or valuable items in storage or heading into storage. Better yet, Artifct what you store. Otherwise, you know what they say...out of sight, out of mind.

When you create an Artifct for the items heading into storage, you can also affix an Artifcts QR code sticker to the box to help you easily recall which box the item went into in its storage location. Bonus! Staring at a wall of boxes? Having an Artifcts QR code sticker on the outside of the box is a quick and easy way to figure out what's in the box without having to open or unpack.

Tag Artifcted items with two tags: one that's simply #Storage and a second that's the specific location, such as #attic, #fronthallcloset, or #storageunit. That way with a single click on any #storage tag you can easily review what you're storing, and second click #attic, and "Oh, yes, that's what's up there. Maybe it's time to take it out of storage and use it."

If you're working with a professional moving and storage company, they usually offer services to help you create an inventory for practical and insurance purposes. We encourage you to consider this the "if nothing else" bare minimum, because we believe you deserve more than an inventory of stuff.

#2 THINK AHEAD TO CAPTURE USEFUL DETAILS

Photos of the objects are important, including from multiple angles, especially if you live in an area prone to natural disasters. But we also recommend a video snippet that gives a 360-degree view if an item is particularly special or valuable. The video may capture details and imperfections you otherwise overlook.

Grab approximate dimensions and weight, too. This will help whether you need to move it again or file an insurance claim.

You may also enjoy our ARTIcles with tips on Articting for Insurance as well as Artifcting for Estate Planning.

#3 ASK BEFORE YOU STORE, THEN STORE, AND STORE SAFELY

We know it might be hard to let go of that piece of furniture that's been in your family for decades or even generations. Likewise, those bins of old papers and photos that you know tell your family's story. It's all very tempting to store for someone someday to enjoy again.

-

-

- If you Artifct it and share it, with one click you can ask someone if they want the item if you do not, using Artifcts as a decluttering app. If they do not want it, you can more easily now let it go to a new home.

- If you choose to store it, and let's assume that space is climate controlled, please still think about what boxes and bins you are storing the item in. So many of the most popular bins you pick up at local shops will let off gasses ("off-gas" in archival terms) and ruin photos, film, and documents. And without proper care, textiles can also be a lost cause. You don't want to realize you lost the history and stored what's now trash. Use archival quality materials. Archival Methods offers great tips and supplies. (Visit Artifcts' Our Partners page for a discount on your next Archival Methods purchase!)

-

Ready to Make Some Decisions?

You’ve read about how long-forgotten belongings can quietly take up space and money, and you now have tools and strategies to track, document, and care for what you store. But real progress happens when you act.

Set aside an afternoon — or even just a couple of dedicated hours — to tackle what’s in storage. Pull things out, see what’s there, and be honest with yourself about what truly still matters. Use Artifcts to capture photos, videos, and stories of the items you decide to keep so their meaning isn’t lost, and let go of what no longer serves you by donating, gifting, selling, or recycling it.

It can feel overwhelming to face years (or even decades) of accumulation — but breaking it up into a manageable block of time turns a daunting task into a meaningful afternoon. Make a conscious decision about what happens next with those belongings, and you’ll not only reclaim physical space but also peace of mind. Your future self will thank you for finally confronting what’s in storage and making intentional choices about what stays and what goes.

###

© 2026 Artifcts, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

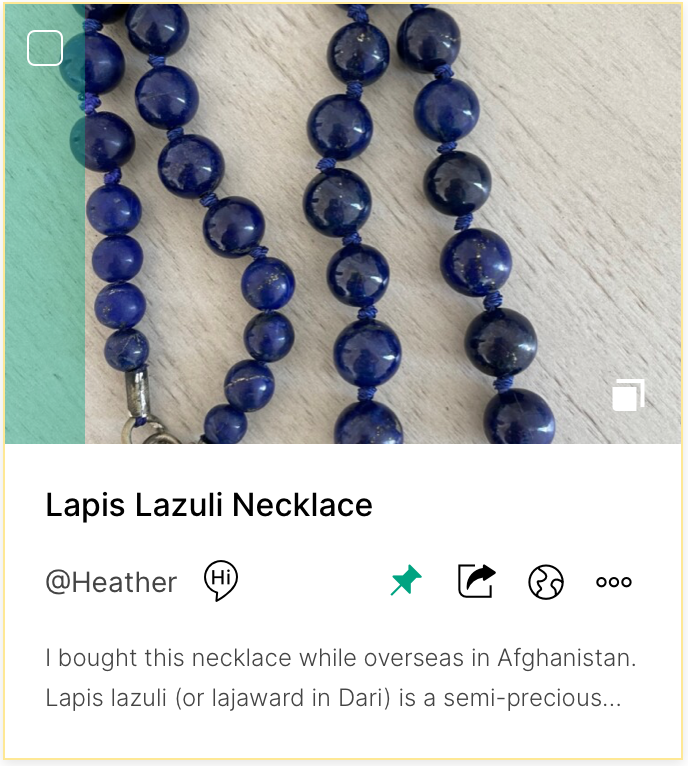

Our 'In the Future' field makes it easy to pass down jewelry and other keepsakes.

Our 'In the Future' field makes it easy to pass down jewelry and other keepsakes.

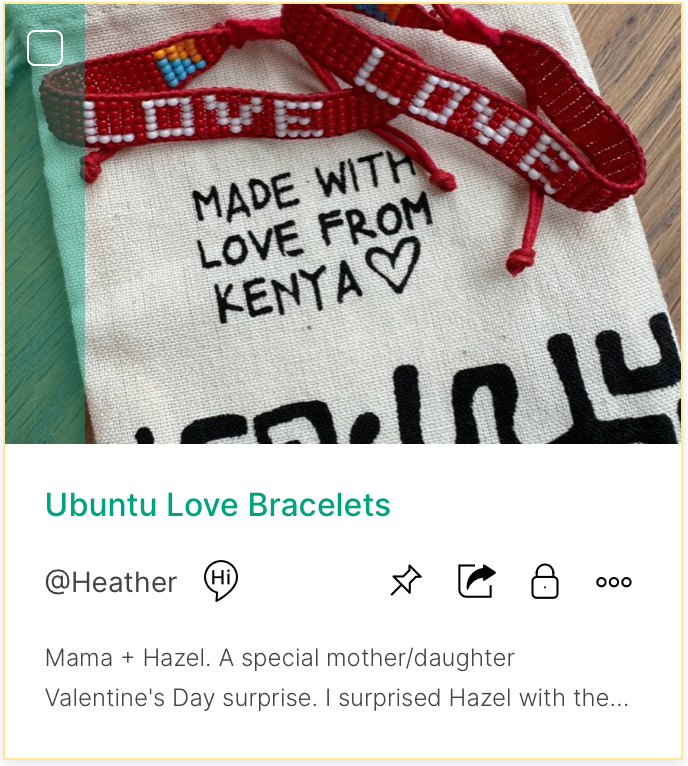

A special Valentine's Day gift from mother to daughter. Sorry, this Artifct is private!

A special Valentine's Day gift from mother to daughter. Sorry, this Artifct is private!